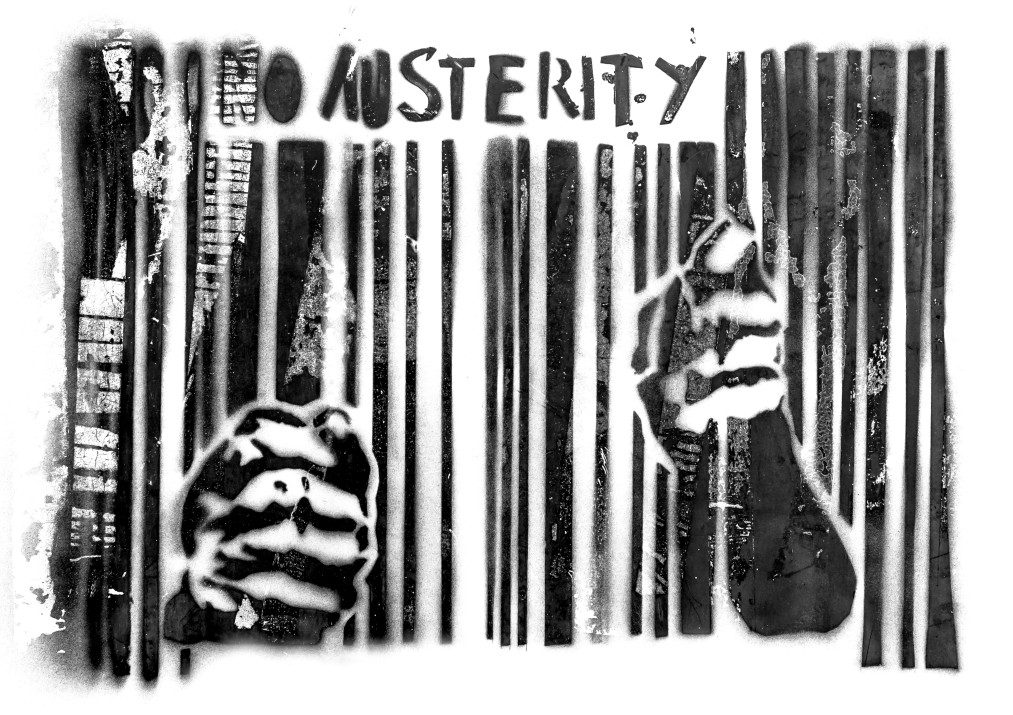

Austerity is known to be a catalyst for increasing inequalities in our societies, but what can we learn from 2008 for today’s economic climate?

The resultant impact of the Coronavirus pandemic could be as much as two million women leaving the workforce.

A 2013 Survey found that female managers stood to miss out on £141,500 worth of bonuses compared with men doing the same role over the course of working life.

As the economic effects of the pandemic intensify gender inequality, it’s our organizations’ actions in the here and now that will shape the barriers to employment and opportunities in the workplace for the future months and years ahead.

There is no disputing the fact that the Coronavirus and the resultant lockdowns and restrictions on our daily lives has had severe consequences for economies and businesses across the world.

In the HR world, in particular, we have been dealing with closed offices, restrictions on movement, furlough, and other labor support schemes, as well as many harsh realities and changes to our day-to-day operations that have put the HR function truly at the coalface.

A staggering report from McKinsey demonstrates that they believe the resultant impact of the Coronavirus pandemic could be as much as two million women leaving the workforce, leading to a huge gender parity barrier in leadership roles in years to come.

They suggest, that while many organizations are providing additional resources related to remote working and employee well-being, there is more to be done to meet employees’ needs for sustainable, flexible, and empathic work environments, especially for parents and caregivers.

Post-2008 there was similarly a back-tracking in regards to women carrying out paid work

Taking a look at the Financial Crisis of 2008 may help us to prepare for what’s to come over the next 12, 18, and likely more months, and what steps we can take in our businesses to perhaps ease some of the unequal impacts this global pandemic will have.

Read more:

Post-2008 there was a back-tracking in regards to women carrying out paid work, regressing to unpaid work, and domestically affiliated work. The Fawcett Society and other research bodies such as a piece from Sher Verick, Deputy Director at the ILO, saw the financial downturn as having different implications on various segments of the population due to the barriers they faced in the labor market. He also saw those hit hardest with jobs in sectors that are more affected by changes in macroeconomic conditions – sectors most affected meaning those such as the public sector which is normally hit the hardest in austerity.

Verick also suggested that “…there is an important gender dimension to the vulnerability of youth in the current [2008] crisis as young men have been generally more affected”, reflecting that these individuals are employed in such sectors as construction and manufacturing, which are also heavily impacted by the recession. He also noted that young women do experience increasing unemployment rates often in a similar fashion to young men, and in some countries, they are in fact the group that suffers the most. This comes on top of the longer-term barriers young women continually face in the labor market.

Despite the arguments of ‘who suffered more’, there was one recurring argument in all the data and analysis from 2008 – that the pay gap and acceptance of women into higher-ranking positions never closed. For instance, the 2013 National Management Salary Survey found that female managers were not only still lagging behind men in terms of pay parity, they also stood to miss out on £141,500 worth of bonuses compared with men doing the same role over the course of working life.’ Furthermore, 8 out of 10 married women (77%) were doing more housework than their husbands according to the Institute for Public Policy Research.

Despite policy being implemented before 2008 such as the Equal Pay Act, women are still severely underrepresented within the work place and underpaid.

In the McKinsey Women in the Workplace study, they found “that the effects of the COVID-19 crisis have exacerbated gender disparities and their implications for women at work, especially for mothers, female senior leaders, and Black women across America. In addition to being laid off and furloughed at higher rates than their male counterparts during the pandemic, women are—notably, for the first time in our research on the topic—considering downshifting their careers or leaving the workforce altogether at staggering rates.”

But there is hope. For example, people are more aware than ever that they need a whole range of skills to remain agile and relevant in a vastly evolving economy and professional environments. The memory of 2008 is not that far away for many and there has been a distinct push for upskilling and reskilling since the financial crisis as the workforce seek to remain agile and relevant in a turbulent business world.

Some have argued as well, that figures for females in the workplace have actually been better than ever, resulting perhaps, from the idea that men created the risk environment that succumbed to the financial crisis in the first place, and therefore potentially that has put more trust and reliance on females, notably in the financial and political sectors, as they are depended to be less ‘risk-takers’ and more responsible than their male counterparts.

What we can see for certain though, is that as the economic effects of the pandemic intensify gender inequality, it’s our organizations’ actions in the here and now that will shape the barriers to employment and opportunities in the workplace for the future months and years ahead.

Get the Editor’s picks of the week delivered straight to your inbox!

Head of UNLEASH Labs

Abigail is dedicated to connecting HR buyers with the technology and tools they need to succeed.

"*" indicates required fields

"*" indicates required fields