Is AI causing a decline in cognitive and creative skills?

“Using AI to generate email responses, answer questions on your behalf, or give you ideas for projects is fundamentally altering your ability to think and do those tasks,” states Lighthouse’s Chief Research Officer Ben Eubanks in his first column for UNLEASH.

Analyst Insight

What if the AI tools used by millions of people every day are actually eroding our ability to think?

That's the question that Ben Eubanks, HR industry analyst and Chief Research Officer at Lighthouse Research & Advisory, asks in his first UNLEASH column.

Read on to get Ben's insight - and stay tuned for his quarterly columns.

What if the tools used by millions of people every day are actually eroding our ability to think?

One of the topics I’ve begun to incorporate into my speaking and education on artificial intelligence is the impact it can have on human cognitive skills and creativity.

A number of different research efforts have begun to produce evidence that overreliance on AI can negatively affect our ability to think and innovate—a concerning prospect.

This happens in a variety of ways. For starters, imagine trying to build a house. You’re trying to put the roof on, but the walls were built quickly and with little effort. It’s likely that the roof will cave in or fall over because it doesn’t have a strong enough structure to hold it up.

That same scaffolding of skills is the focus here.

If someone is using generative AI tools early in their career and gets to a point where their job isn’t as routine and predictable, will they be able to perform their work?

Within the HR context, a parallel is this: many of us that work in the HR world started out in the file room.

We saw how processes worked, how decisions were made, and what the flow of information looked like.

Then, as we matured in our careers, we could make our own decisions with judgment and insight based on those early experiences.

But if we skipped all of that experiential learning because AI was handling it, could we truly make an intelligent decision as a manager, Director, or VP of HR if we didn’t have that foundational knowledge?

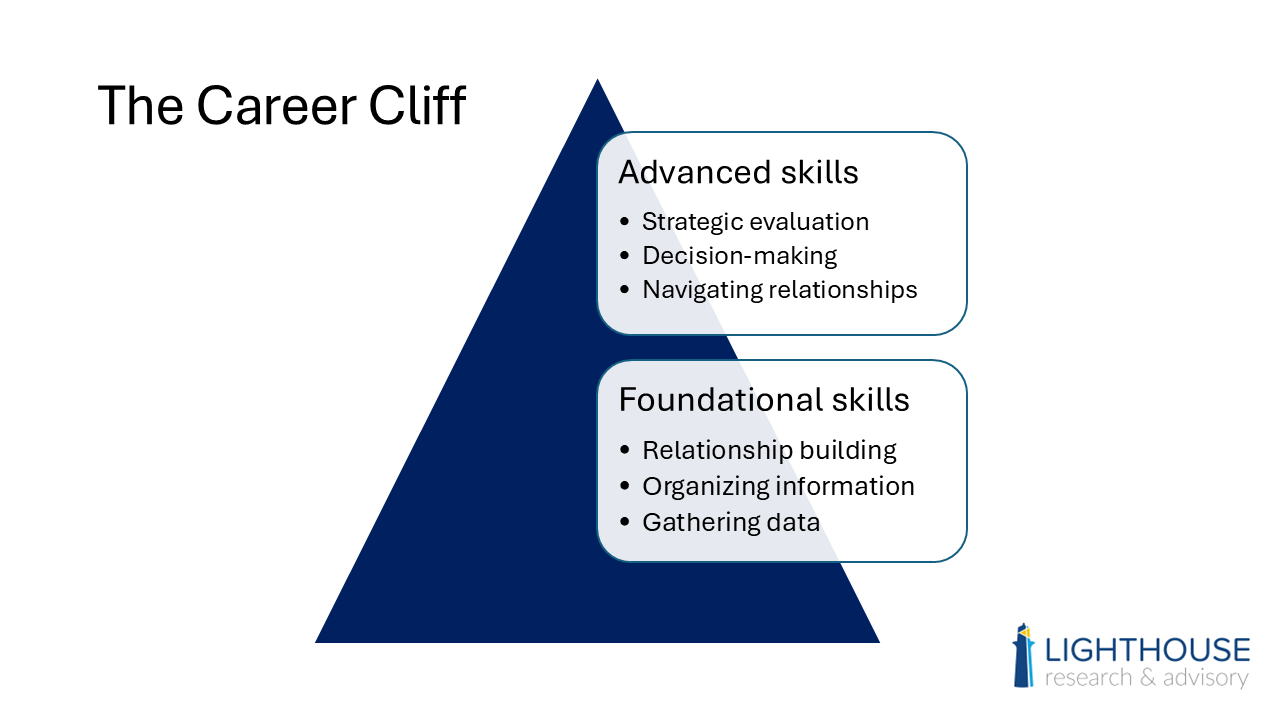

Put simply, foundational skills are needed as a basis for establishing more advanced skills, and that’s the reason one group benefits most from generative AI in the workplace.

Who benefits more from AI? Experienced workers or younger ones?

In spite of the common talk track that younger/junior workers are better at technology and can teach their more experienced, older peers how to use the tools, the data seem to indicate that won’t happen with AI.

It’s not because younger workers don’t have AI expertise—it’s because they don’t have the work experience and technical skills to get the most out of the AI themselves.

When I speak at conferences and at internal HR team strategy sessions on this topic around the world, that’s one of the areas I highlight.

Someone with more experience will be able to get more out of these generative AI systems because they know better questions to ask.

For comparison purposes:

- Junior HR team member question for generative AI: “What is the reason our turnover is so high at my company?”

- Senior HR team member question for generative AI: “We’ve seen a 10% increase in turnover for the last two quarters at our manufacturing firm. Our compensation is above market rates, so what are four potential areas we could examine to determine the causes of rising turnover?”

Going deeper lets users get more from the interaction and a much more complete answer.

It gives an edge to the more experienced professional that knows what happens next, then what happens after that, and so on.

That’s a silver lining, but the truth is that this still has negative side effects that research is just beginning to uncover.

Crushing creativity: New insights from the University of Toronto

It all comes down to laziness. Not the ‘sitting on the couch eating snacks’ laziness, but the natural mechanisms our brains use to moderate and manage our daily activities.

Our brains are wired to conserve energy.

When we’re giving the brain signals that something is taken care of, it stops putting effort and focus into solving it.

A small daily example of that: exactly how long did it take you to tie your shoes that last time you put them on?

We don’t know, because it’s not important in the grander scheme, so our brains don’t retain that information.

Unlike some topics I speak on, this one can make people defensive, especially if they’re using generative AI tools to support their work and tasks on a regular basis.

The most common response I get is ‘I used to remember phone numbers and now I can’t because I have a cell phone. Should I quit using my phone?’

It’s common to also hear a similar question about calculators versus mental math.

The difference in this discussion about AI and those examples is that remembering a phone number or doing some quick math is now easier because we don’t have to memorize, but it doesn’t fundamentally alter our ability to think.

Using AI to generate email responses, answer questions on your behalf, or give you ideas for projects is fundamentally altering your ability to think and do those tasks.

At a fundamental level, AI is reshaping how we process information and make decisions, often diminishing our reliance on our own cognitive abilities.

One study from the University of Toronto showed that usage of large language models and generative AI systems reduces the ability for humans to think creatively, resulting in more homogenous, ‘vanilla’ ideas and fewer truly innovative ones.

The researchers found that while these tools can enhance short-term performance, they may reduce humans’ ability to think independently and creatively over time.

Researchers likened this effect to a temporary boost in ability, similar to performance-enhancing tools in other fields, which might come with hidden costs.

The study examined two aspects of creativity: divergent thinking (generating multiple ideas) and convergent thinking (finding connections between unrelated concepts).

Participants were divided into two groups.

One group used GPT-4o, an advanced LLM, during a training phase, while the other worked without AI assistance.

Initially, participants using GPT-4o performed better, producing more ideas and faster solutions.

However, when both groups completed tasks independently in a subsequent test phase, those who hadn’t used the AI outperformed the AI-assisted participants.

The researchers attributed this to a homogenizing effect, where repeated exposure to AI-generated ideas reduced the variety and originality of participants’ thinking.

Interestingly, this narrowing of creativity persisted even after the AI was no longer used.

Think about that. Even when someone quits using these tools, their lowered creativity persists for some amount of time.

It’s likely that it would need to be rebuilt like a muscle or a habit, but the research hasn’t yet explored that aspect.

These findings highlight the need for thoughtful design of AI tools, and other studies look at similar types of impacts in an education setting, showing that students using AI for practice tests cannot perform as well on the actual exams.

While LLMs clearly offer benefits, such as improving performance during use, their influence on long-term cognitive abilities raises important concerns.

The study emphasized the importance of developing AI systems that not only support creativity in the moment but also encourage diverse and independent thinking over time. The implications extend beyond individual users.

As AI becomes more integrated into creative processes, it could shape cultural and societal norms.

Ensuring that these tools enhance, rather than restrict, human ingenuity will be critical as we navigate this evolving relationship between humans and AI.

Let’s close with a final piece of research that is directly related to the work of HR.

Recruiters using AI can ‘fall asleep at the wheel’

Harvard Business School’s Fabrizio Dell’Acqua wanted to understand how AI tools would impact the work of recruiters.

He gave four different groups of recruiters access to strong, good, bad, or no AI tools and observed their work.

Those with the strong, highly predictive AI were much more likely to metaphorically ‘fall asleep’ at the wheel with the AI driving.

Those with the ‘bad’ algorithm were more likely to invest their time and effort into confirming recommendations and making decisions.

Translation: the more powerful and capable we believe an algorithm to be, the less we want to invest our own time, effort, and expertise into the task.

When we think it’s not that great, we’re more likely to work in tandem with the algorithm to come to a confident conclusion.

Ultimately, the blended and complementary strengths of humans and of algorithms are better than either raw human effort or brute force AI alone.

In the end, we have to consider these potential downsides of AI as we are evaluating them for usage in HR and other areas of the business.

For some time, bias and data privacy have been the primary reasons employers were concerned about AI usage.

Now, we have a potentially even more worrisome set of consequences to consider and mitigate if artificial intelligence is to be used within our organizations in the future.

Sign up to the UNLEASH Newsletter

Get the Editor’s picks of the week delivered straight to your inbox!

Chief Research Officer, Lighthouse Research & Advisory

Ben Eubanks is a speaker, author, and researcher. He's Chief Research Officer at Lighthouse Research & Advisory.

Contact Us

"*" indicates required fields

Partner with UNLEASH

"*" indicates required fields